Along with the many plaudits marking the 75th birthday of the NHS, came much chatter about its many problems and questions about its survival. It has been seen for decades as a problem child, devouring all the resources, achieving poorer and poorer outputs, and doggedly refusing to change. It is forever being used as a political football and fodder for negative newspaper headlines. It suffers an endless barrage of top-down directives to improve (or die). The debate never changes and the “need for transformation” is trumpeted endlessly by every would-be expert.

It’s like looking in a mirror!

Ironically, this conversation reminds me of many a clinical discussion I was party to when I worked in multi-disciplinary teams in the NHS, where we talked about “problem patients” who wouldn’t “comply” with treatment and “refused” to change their lifestyles. Their survival was often in question, and we all shook our heads helplessly, tacitly blaming the patients for not “engaging” in the treatment we “knew” would work for them!!

Problems are the problem!

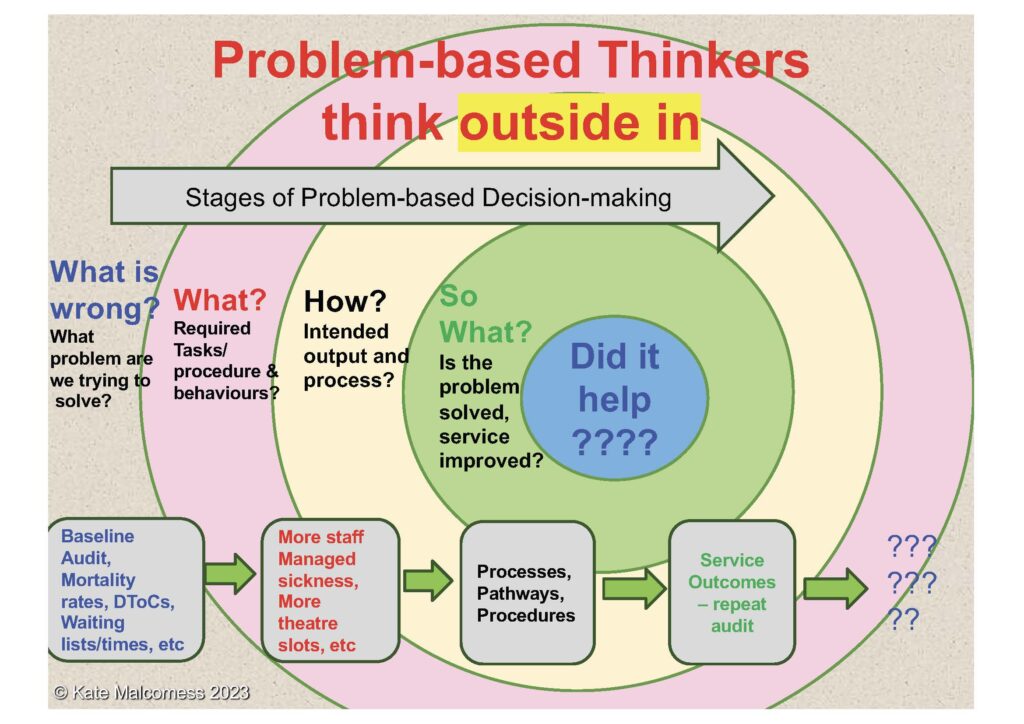

Problem-based decision-making has dominated most clinical decisions in the NHS since its inception and, despite evidence to the contrary, it also dominates most of the quality improvement methodologies used to try and “transform” the organisation.

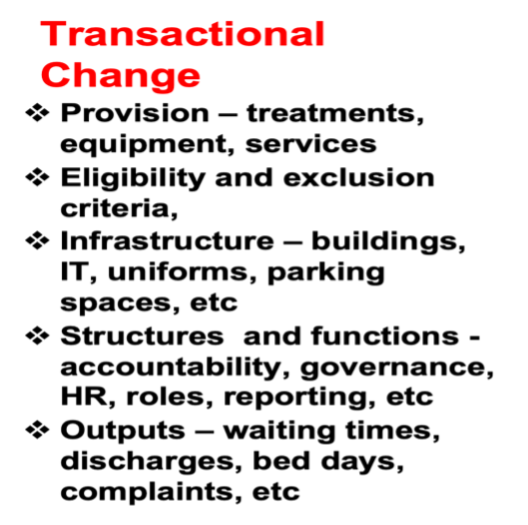

Transactional change methodologies are known to be very limited in their effectiveness – they lend themselves best to simple problems or processes, not huge, complex systems – much like problem-based medicine, which was developed when life-saving interventions dominated health care and complex co-morbidities were rare.

In clinical practice, an attempt has been made to address this out-dated science by heralding “patient-centred” care as the new horizon, that goes beyond problems and deficits. However, in a system that is entirely focussed on problems, patient-centred approaches have become mired in custom-and-practice. Discussions often default to asking people to articulate the problems they want to fix. These conversations are dominated by questions like: “What are your goals for treatment?”, “What would you like to work on?” “Which of your many issues impacts you most?”, “What would you like to be able to do better?”. These are not person-centred conversations, they are problem-based conversations masquerading as patient-centred and tend to end up in the same place – i.e., Do you “fit” our criteria? Can we “fix” your problems? Can we stop you doing risky things? Can we persuade you to engage in treatment? and how do we make sure we ensure we meet our targets?

The emperor is naked!

Most organisational change approaches are lauded as transformational, but they operate in exactly this way. The questions they start with are problem-based. The problems are myriad but include the headline-grabbing and highly rehearsed,

- Long waiting lists and times,

- No access to GPs

- Hospitals on red alert, at 110% capacity with no beds,

- Ambulances stacked up at A&E,

- Doctors moving to Australia.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) usually seek to address these problems by setting targets for improvement that are often activity or process based e.g. reduce waiting time, reduce delayed transfers of care, increase number of visits in a day, etc. Quality improvement questions typically then relate to “how do we improve things so we can meet our KPI’s”. Tautology at its most paradoxical!

This approach to change results in an environment of relationships that is dominated by fear and anxiety, defensive practice across all aspects of operations and a limited ability to think or learn. It also results in a workforce that is increasingly drained and burnt-out, and leaving the NHS in droves.

Whilst most recognise that the out-dated Newtonian “science” dominating the NHS is not fit-for-purpose, the alternative Quantum “science” seems to be too scary! But in seeking certainty and pinning it down, in the belief there is a right and wrong way to do things, we depersonalise our decisions and lose reason, autonomy and choice. This, in turn, impacts very negatively on organisational resilience.

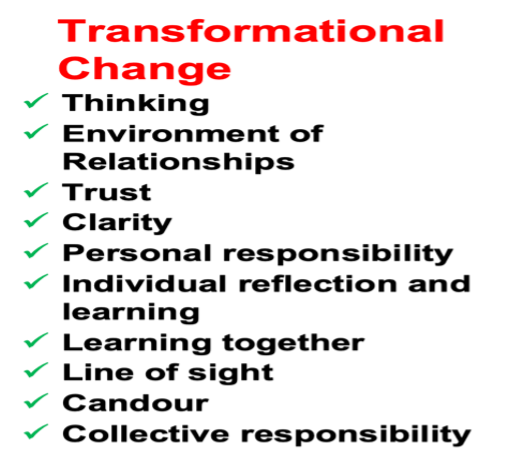

True transformation would involve embracing the science of safe uncertainty, of negative capability and of continuous discovery and learning. It would require a readiness at the highest levels of power (i.e. the civil service) to let go of “controlling” and micro-managing an organisation of 1.5 million people, and recognise and trust the intelligence they can gain from starting with what matters to the people working for them.

We must transform how we think and relate.

To achieve true transformation, in either clinical practice or in the organisation of the NHS, the most important things that need to change are the culture of relationships and how we think. The culture must move from a reductionistic, transactional approach to change to one that is truly transformational. It needs to transform the environment of relationships in which people function, changing how we make decisions, how we all relate to each other and the outcomes we all expect from each other.

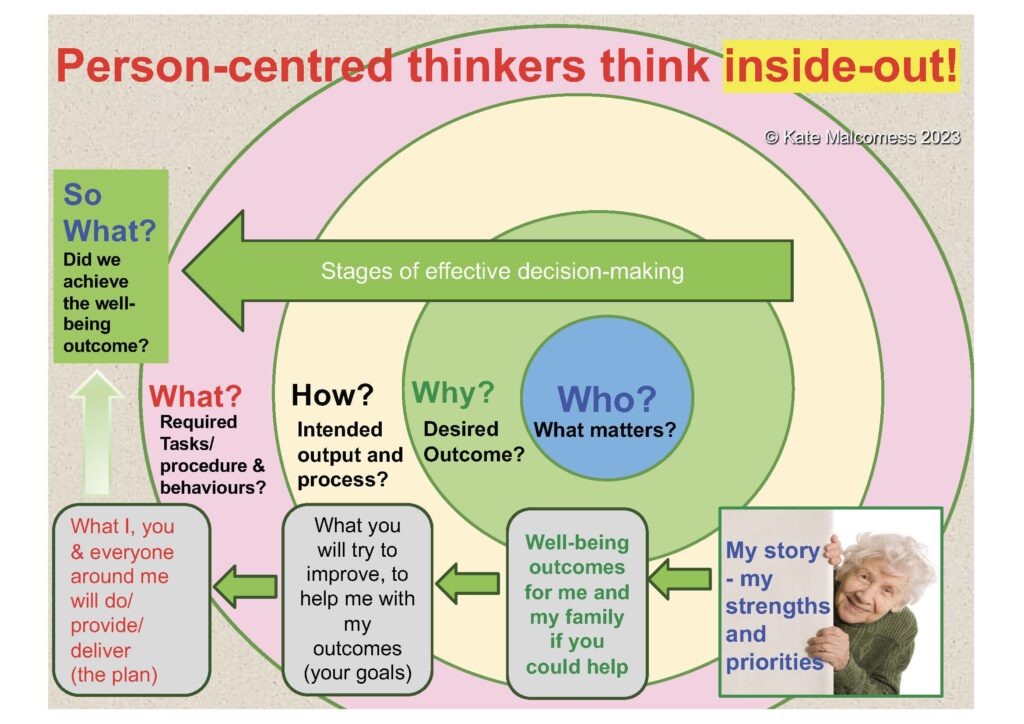

Taking a person-centred, outcomes-driven, strengths-based approach to clinical decision-making has been shown to be highly effective in producing the health and well-being outcomes that matter to people and in improving people’s journeys through, and experiences of, services. It also improves the well-being of the workforce. They report feeling less helpless, less anxious, and much more fulfilled in their work.

Starting with what matters to a person, not in terms of what’s wrong with them, but in terms of what is important to them, to their families and to their communities, means all practitioners must listen first.

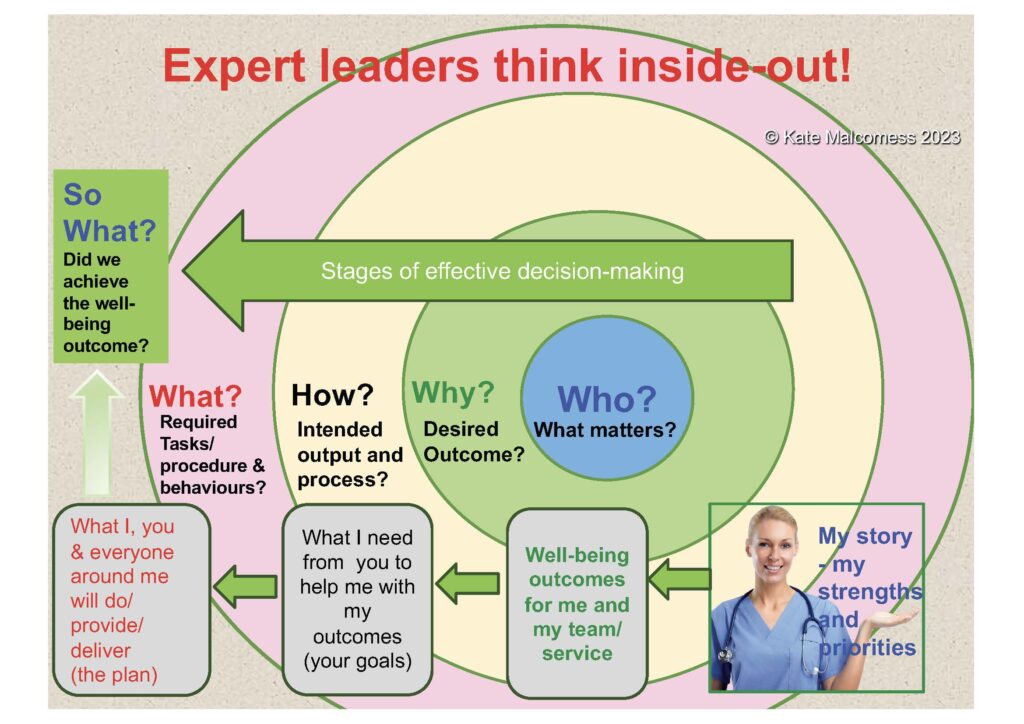

They listen to make sense. Listen for the strengths and resources the person, their family and community bring to the situation. Seek to understand the fears and worries they are all expressing, and work towards a mutual understanding of the outcomes that would satisfy the person and those most proximal to them, before agreeing the interventions that might help achieve these. They change the order of clinical decision-making!

This change in thinking represents a transformation in the clinical contract i.e., a fundamental shift in the culture of relationships that represents clinical care. Gone are the transactional contracts of: clinician – patient; provider –“customer”; specialist expert – helpless ignoramus; inadequate resources – unrealistic expectations. Gone is the eye-rolling, helplessness of MDT meeting of yesterday year. In their place is active partnership with a mutual understanding of intended personal outcomes and a co-creative approach to discovering possibilities for change.

We need Radical Change

So, could we dare to take a person-centred, outcomes-driven, strength-based approach to organisational change? Could we ensure the NHS not only survives but thrives for the next 75 years?

It is possible! I have seen it happening in pockets (mostly in the devolved administrations of the UK).

It does, however, take a willingness from everyone in the system to change their thinking. It requires a fundamental shift in organisational intelligence and involves building on the emotional and relational capability of leaders. Helping them start with the person (the member of staff in this case), to trust in their strengths, work at understanding what matters to them, help them address their fears and together define the outcomes for the NHS that they would all be satisfied with.

Outcomes that would help everyone in the system achieve their best work and make them proud to work for the NHS. Compassion is not enough, really listening to understand, equal partnership and true co-production are all required.

The NHS has all the resources it needs!

The greatest strength of the NHS is its people. I have learnt in my experience of over 35 years of working with tens-of-thousands of NHS staff and leaders (across all disciplines, contexts, and regions, from cradle to grave), that the vast majority come to the NHS passionate about making a difference, driven by an innate wish to learn and improve outcomes, and with strongly held ethical beliefs that define their meaning and purpose.

What if??

What if we simply stopped seeing the NHS as the “problem child” and recognised the NHS, not as an entity but, as a collection of highly dedicated people? What if we stopped shaking our heads helplessly, tacitly (and often overtly) blaming “the NHS” for not “engaging” in the improvements we “know” would work? What if we released them to lead the transformation, by trusting them and holding them in an environment of relationships that supported their best work? We would be amazed at the new life, energy and abundance of goodwill this would bring.